Where should you play your best batsman?

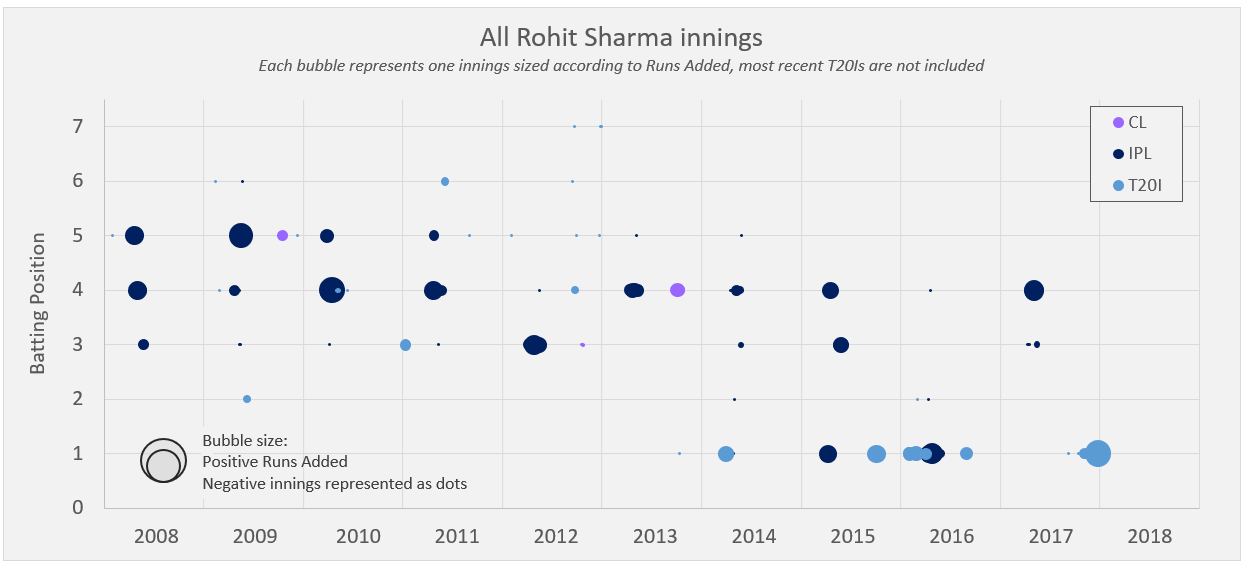

Rohit Sharma is the captain and assumed best batsman of the Mumbai Indians. He seems likely to bat at number 3 or 4 this season, unchanged from last year, when Buttler and Patel were generally preferred as the opening pair. Whilst those two are now gone, Mumbai did acquire another well-established opener at auction in the form of Evin Lewis, Ishan Kishan may also get the chance to impress

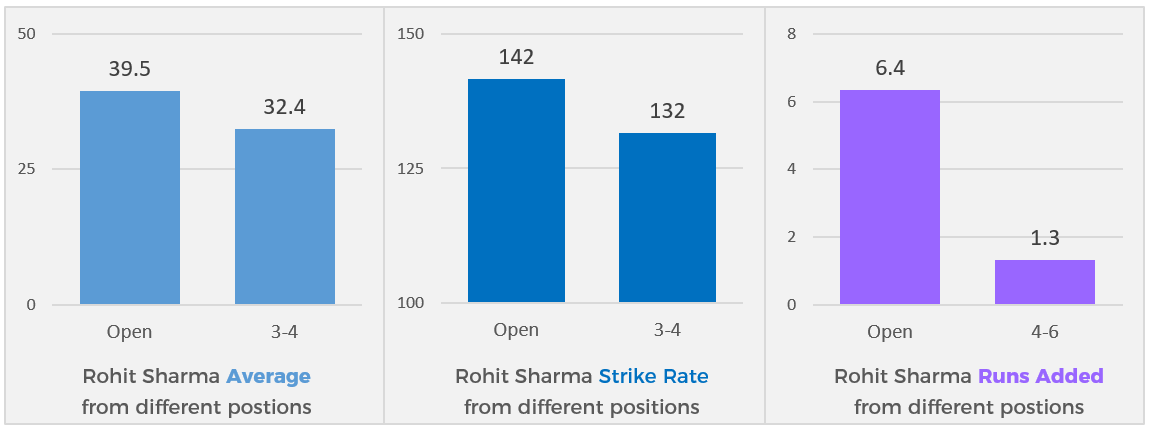

Last year, Sharma suggested that “probably three, four is the best position” for him but the stats emphatically disagree. In 52 matches as an opener, he averages 39.5 runs at a strike rate of 142. Both numbers drop noticeably when he arrives between 4-6, falling to an average of 32.4 runs at 132 (in 130 matches)

It is worth noting that simple averages and strike rates don't account for match situation. The opening batsmen have the advantage of planning through the Powerplay, where the fielding restrictions make it easy to score and easier to survive

We can also use more advanced metrics to assess Sharma’s best position. Runs Added is my metric that estimates how a player’s actions impact the team total – encompassing how fast they score, how long they bat for, and, most importantly, the match situation. Sharma creates +6.4 Runs Added per game when he plays at the top of the order... elite level. Yet when he arrives at three or four, that drops all the way to +1.3 Runs Added per game

All the metrics available are saying that Rohit Sharma should open the batting. Case closed, right? Not necessarily. It turns out that almost all batsmen have better stats as an opener

It often seems that batsmen produce their most impressive figures from the top of the order. A recurring theme whenever I analyse individual players. And we can confirm this by looking at batsmen who have played up and down the order throughout their career...

I identified players who have played at least 10 matches as an opener and at least 10 matches from later in the order, at slots 4-6. This deliberately excludes the number three position, after my analysis showed that the number three position was more similar to opening than anything else. And excluding it allowed me to draw a more obvious distinction between opening and middle order batting

The qualifying list includes mostly well-known names, ranging from AB to Zondo, who have fulfilled a range of responsibilities for their teams. Focusing on these players helps account for the fact that teams might play better players at certain positions. We can look at each individual and see how their performance changes depending on where they play

Just looking at the scales on the axes of this chart should give an idea for how much easier it is to produce impressive innings from the top of the order. None of the included players have managed to average more than 1.5 Runs Added when batting from middle order positions. Yet there is almost an entire XI averaging 5+ Runs Added per match

The dotted line gives a rough guideline for how much we can expect an top batsmen to produce later in the order, given their history as an opener. Rohit Sharma is exactly where we would expect him to be. Right next to him is his captain for India and just a little further up the line is Jos Buttler - the man who took on opening duties last year for the Mumbai Indians. Despite significantly better numbers as an opener, it is perfectly defensible for Rohit Sharma to suggest that playing further down the order is optimal

Looking at some of the underlying stats can help us to understand this better. The below charts use a very similar group of players (at least 15 matches at both 1-3 and 4-6) to show how expected averages and strike rates change as an experience T20 batsman moves up and down the order

Averages gradually decrease as players move down the order. The only exception is the #1 batsman. Perhaps because they often face the opposition's best bowler and have little time to judge the pitch before facing their first ball. That lower order batsmen have lower averages is hardly surprising as they have less time in the Powerplay to build a big score

Strike rates are also fairly consistent – just 8 runs per 100 balls separates the highest position (2) from the lowest (5). Again, it isn’t too hard to guess what is happening… the early batsmen get the Powerplay whilst the later batsmen get to slog out the death overs. Unlucky #5 experiences the worst of both worlds

Even the advanced metrics favour opening batsmen. More so, in fact. The variation in True Strike Rate is greater than the variation in traditional Strike Rate. We now have a difference of 19 runs per 100 balls versus just 8 runs before. And Runs Added is barely an improvement on basic average, once again, decreasing as we move further down the batting order

The experience factor cannot be completely discounted as an explanation for these results. Whenever a player was opening for his team, his average experience at that point was 84 T20 matches, compared to 58 matches for the #6 position. Batsmen are ‘promoted’ to the top of the order as their careers progress. But there isn’t much strong evidence that this has any impact. The cause-effect relationship could also work the other way around. We also shouldn’t ignore the possibility that opening batsman enjoy longer careers precisely because their performances look more impressive at the top of the order

It simply isn’t fair to compare stats for late order batsmen against openers. Despite using more sophisticated metrics, which supposedly adjust for the match situation and for the fielding restrictions, opening the batting genuinely seems to be a significantly easier job than powering the middle order

Why are the supposedly more advanced metrics failing to help here? True Economy adjusts scoring rates by over and Runs Added also accounts for wickets. Yet opening batsmen still have a clear advantage

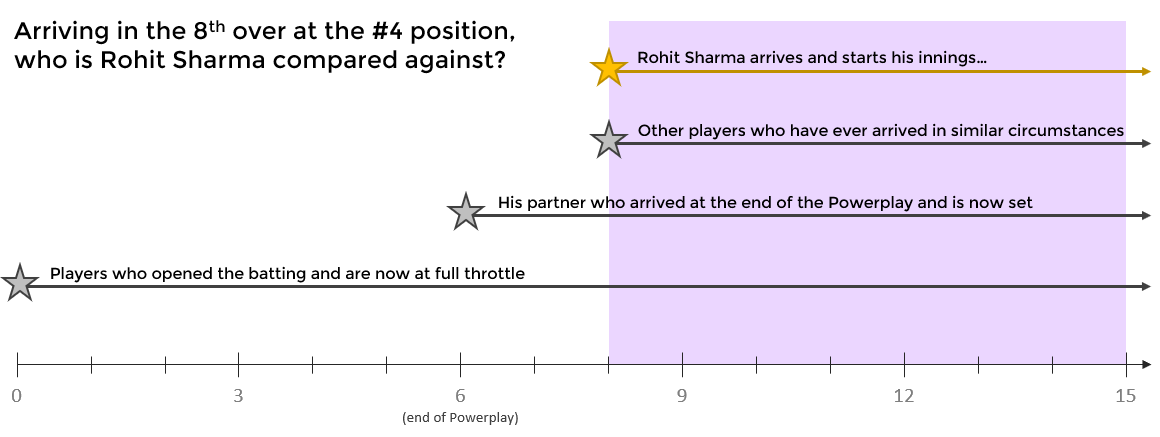

When we calculate these metrics, we are comparing the players against others who have batted in similar situations. If Rohit Sharma is playing at #4 and arrives at the crease in 8th over, then his performance is rightly being compared to others who arrive in similar situations. But he is also getting compared to batsmen who have been at the crease for several overs and may already have found their top gear

This does not mean that advanced metrics have no value. True Strike Rate is one of the five key metrics that I want to quickly evaluate player performance. But we do need to be careful comparing players who adopt different roles for their teams. This is the main reason why average batting position is another of those five key metrics: I have yet to find a way to construct a metric which is completely independent of a player’s role with their team. Understanding that role is vital before starting to look at any other numbers

When analysing whether Rohit Sharma should open the batting or strengthen the middle order, it would be incorrect to accept his stats for each position at face value. Whether using basic metrics or more advanced ones. It is also important to consider who else in the team can fill those roles: Where are they strongest relative to Sharma? What is the best ordering to maximise value at every position?

The Australia national team has an unbelievably talented group of T20 batsmen to chose from. They have four world-class players who usually open for their club sides: Chris Lynn, Aaron Finch, D'Arcy Short, and David Warner (I started writing this quite a long time ago). They also have Glenn Maxwell... who I would argue is the best of the bunch

Glenn Maxwell is usually regarded as a middle order batsman. In the data that I am using, he played at positions 4-6 far more often (on 112 occasions) then at positions 1-3 (on 40 occasions). Like Sharma, he produces more value as an opener than later down the order. Far more value. In his most recent matches as an opener, he delivered +11, +17, and +72 Runs Added

The argument could easily be made that Maxwell is the best opening batsman in the world, despite very rarely playing that position. He starts rapidly (122 SR within the first 6 balls). He has a momentous top gear (184 SR after 18 balls faced). And he is consistent against both pace bowling (+29 True Strike Rate) and spin (+38 True Strike Rate). With a trend towards more spin in the Powerplay, that consistency is more important than ever for an opening batsman

But those attributes are all useful for a #4 batsman too. And as we have seen – the opportunity cost in the middle overs is much lower. We also need to consider what other players in the team can do. Not all those Australian guns can open the batting. We need to chose two

Firstly... wow. Remember that entire XI averaging 5+ Runs Added per match? Four of them are Australian. Those four batsmen (Short hasn't played enough yet) could not be much further to the right-hand side of that chart

Based on that chart, Aaron Finch should clearly bat in the middle order. Like Maxwell, he is equally strong against both pace (+32 True Strike Rate) and spin bowling (+34 True Strike Rate). And with Finch in the middle order, Chris Lynn, the ravenous right-arm pace monster, should open

My inclination is not to take Maxwell's incredible opening stats at face value. His is a smaller sample than Lynn's and, amazing as they are, his stats as an opener are likely to regress to the mean. On the other hand, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that he is the second best middle order batsman in the team, followed closely by David Warner (who is banned anyway)

More often than not, the best batsman on the team should open the batting. It gives them to chance to get set whilst the fielding restrictions are still in place. They will last for longer and they will face more balls, allowing them more opportunities to influence the outcome. But almost all players benefit from the chance to open the batting - no matter how good they are - the key is finding the players who it benefits the most

My opinion is that Mumbai should open with Rohit Sharma. Spin may be on the rise but Powerplays still feature disproportionately more pace bowling. Sharma sometimes struggles to score against spin (-15 True Strike Rate), whilst being extremely productive against pace (+16 True Strike Rate). And unlike the enviable options open to the Australian team, Mumbai have fewer established opening batsmen and a packed late middle order (Pollard, Hardik, Krunal)

Just don't do it because his runs, average, strike rate, True Strike Rate, and Runs Added all improve at the top of the order. There is a lot more to consider